directed by Clive Barker

1987, 93 minutes

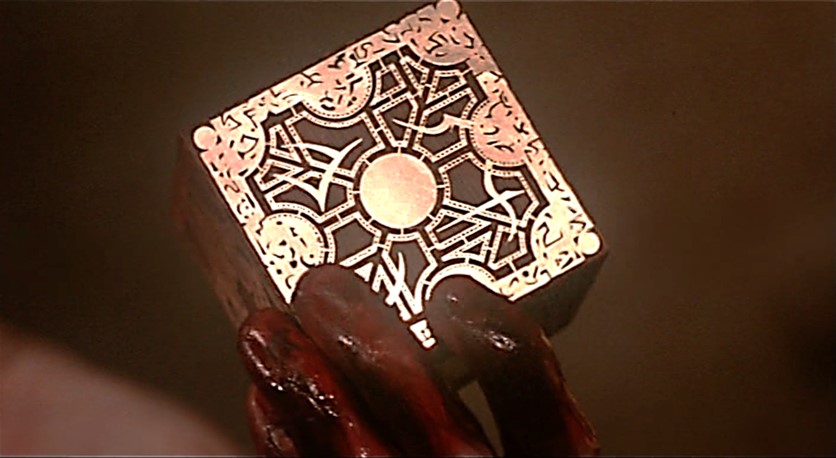

Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman) is killed when he solves a puzzle box which summons the demonic Cenobites. When his brother Larry (Andrew Robinson) moves into the house where Frank died the blood from an accidental cut brings Frank back to life. Larry’s wife (and Frank’s former lover) Julia (Claire Higgins) seizes the opportunity to escape from her dull marriage by completing Frank’s resurrection.

1987 was a very good year for Clive Barker. His directorial debut ‘Hellraiser’ scored at the box office and his first full-length fantasy novel ‘Weaveworld’ reached the bestseller lists. Horror fiction was huge in the eighties. Stephen King dominated the genre so when he hailed Barker as the “future of horror”, the market took notice. With the rise of home video horror cinema was booming too. Obscure European shockers and arthouse sleaze seeped into the sitting rooms of British suburbia and onto the front pages of indignant tabloids. Whilst Thatcher and Reagan re-engineered public morality with their extreme brand of conservatism, subculture of all shades blossomed. When eighties pop heroes Frankie Goes to Hollywood proclaimed that we were “living in a world where sex and horror are the new gods”, we believed them. Very little of the horror product being consumed in Britain was home-grown. There was a strong literary scene ranging from the heavy metal pulps of Shaun Hutson and James Herbert to more nuanced writers like Barker’s fellow Liverpudlian Ramsey Campbell but most horror cinema came from the US, or from Europe. Hammer had fizzled out in the late seventies, so the arrival of a British made horror film was quite an event, but to describe ‘Hellraiser’ as a British film is misleading; it was funded by eclectic US film distributor New Line, who expanded into film production during the eighties. The huge commercial success of their ‘A Nightmare on Elm Street’ (Wes Craven, 1984) made them aware of horror’s commercial potential and Barker’s rising star seemed a good proposition. New Line’s concerns about marketing a British film in the US meant that major roles were filled by US actors whilst British support players were redubbed.

Before ‘Hellraiser’, Barker had considered two other possible film projects but passed them on to George Pavlou, another aspiring director: ‘Underworld’ (1985) and ‘Rawhead Rex’ (1986) were hogtied by miniscule budgets and, despite Pavlou’s obvious enthusiasm neither film captures the originality or vigour of Barker’s prose. Disappointed, he decided to film his novella ‘The Hellbound Heart’, admitting that he had very little idea of how to direct a feature film, having only made experimental shorts ‘Salomé’ (1973) and ‘The Forbidden’ (1978). Barker made up whatever he lacked in experience with an abundance of creativity. ‘Hellraiser’ is an ambitious film that feels as if it is constantly striving, like Frank, to become something more. Barker’s elegant prose and his superb cast lift the film. Strong female characters are a notable feature of Barker’s fiction and Claire Higgins delivers a show-stopping performance, giving Julia just enough humanity for us to feel some sympathy, despite her actions. Barker stumbles a little, the novella culminates in the resolution of Frank’s deal with the Cenobites and ‘Hellraiser’ should have ended at this point too. Instead, it approaches farce as Kirsty engages in rubbery fisticuffs with a demon whilst attempting to banish the forces of darkness. This underwhelming climax blunts the film’s edge, but Barker’s approach is so energetic and original that we forgive his occasional misstep.

Barker, with his background in avant-garde theatre creates an intensely theatrical, almost ritualistic experience. Despite the trappings of kitchen sink drama ‘Hellraiser’ often feels closer to Jacobean revenge tragedy or mediaeval mystery play with its focus on bargains, bloodshed, martyrdom, and miracles. You can almost hear the creaking of stage machinery, but this is not adverse criticism: Bob Keen’s ingenious mechanical effects, elaborate make-up design and Joanna Johnston’s costumes demonstrate that creative passion can work wonders on a shoestring. Occasionally the handmade illusions falter (look out for the trolley wheels that drive the unconvincing ‘engineer’) but most of the mechanical effects are stunning. Frank’s resurrection is a symphony of pulsing veins, oozing pus, and thrusting bones. His unfinished form references the intricate anatomical studies of Andreas Vesalius. Composer Christopher Young’s sweeping, fin-de-siècle orchestrations amplify the film’s sense of ritual, his score is an object lesson in the power of music to influence cinematic style and tone. As originally scored by electronic experimentalists Coil ‘Hellraiser’ would have been a very different experience. The Cenobites quickly became iconic, catching a cultural moment as rubber and leather fetishism entered the fashion mainstream. They look back to the spiky aesthetic of punk and forward to current fashions in body modification which have seen tattoo and piercing parlours emerge from basement and backstreet into the shopping mall. Sculptures in flesh, bone and sinew, the Cenobites are a distorted reflection of wealthy twenty-first century consumers’ pursuit of physical perfection through cosmetic surgery. David Cronenberg had depicted the mutation of the human body in ‘Videodrome’ (1983) and ‘The Fly’ (1985) but Barker’s treatment of the flesh is more theological than technological. ‘Hellraiser’ calls to mind the writings of Georges Bataille who, like Sade and Foucault places sexuality at the centre of philosophical debate. In ‘Eroticism’ (1957) Bataille contemplates man’s pursuit of spiritual transcendence through violence, incest, and other deliberate breaches of social taboo. Frank’s violent apotheosis has blasphemous echoes of the crucifixion but also suggests the notorious photographs of the Leng T’Che found in ‘Tears of Eros’ (1961); Bataille’s presentation of these images, his interpretation of them, indeed the whole body of his work remains contentious and subversive in the extreme. If Bataille had established a religious movement Barker’s Cenobites would be its high priests.

Unfortunately, neither of Barker’s subsequent film projects fulfil the promise of his debut. ‘Nightbreed’ (1991), is enthusiastic but messy; the film was recut by nervous studio executives, but its long-awaited reconstruction is not much better. ‘Lord of Illusions’ (2001) is a neater film but feels aloof and lacks passion. Since the release of ‘Hellraiser’ Doug Bradley’s lead Cenobite has developed a cultural life of his own as ‘Pinhead’. Insatiable fan demand for more from Pinhead along with the film industry’s refusal to let a good thing die in peace has spawned multiple, increasingly redundant sequels. Only the first, ‘Hellbound: Hellraiser 2’ (Tony Randel, 1988) has any merit. It benefits from another fearless performance from Claire Higgins and a memorable turn from Kenneth Cranham who competes with Doug Bradley for the best lines. Continuing where the first film left off, it has a similar style and provides closure for the major protagonists. It’s clear that Barker, as executive producer retained some paternal interest but was keen to be done with these characters so he could move on to fresh material. Some of Barker’s short stories (published in a series of six ‘Books of Blood’ from 1984 to 1985) have been filmed. Most notably Bernard Rose scored a hit with ‘Candyman’ (1992), recently remade by Nia DaCosta and adapted from Barker’s story ‘The Forbidden’, but none of these films contain much trace of Barker’s unique voice. To rediscover the vaulting ambition and transgressive energy of ‘Hellraiser’ viewers should seek out Barker’s novels, where his prodigious imagination can stretch its wings and take flight.

In 1998 Barker acted as Executive Producer for Bill Condon’s ‘Gods and Monsters’ based on Christopher Bram’s novel about the death of James Whale (Ian McKellen), the director of ‘Frankenstein’ (1931). The parallels between Whale and Barker are striking: Both gay men whose precocious and polymathic artistic talent enabled them to escape lower-class British childhoods for careers in Hollywood. In ‘Gods and Monsters’ Whale is clearly frustrated that his iconic design for Frankenstein’s monster has eclipsed the rest of his career. Barker may feel similarly ambivalent about Pinhead; his tired, belated return to the Hellraiser universe in his novel ‘The Scarlet Gospels’ (2015) is a lacklustre and depressing affair. Stephen King was correct. Clive Barker was ahead of his time, but his creativity was stifled by conservative studio politics and undemanding fandom. Thankfully horror culture is changing. Franchise juggernauts like ‘Halloween’ or ‘Insidious’ may continue to milk formula but newcomers like Ari Aster and Robert Eggers have demonstrated that there is enough room for cerebral, visionary filmmakers who are not afraid to challenge as well as entertain. ‘Hellraiser’ pointed the way and remains exhilarating, uncompromising cinema.

Quotes:

“We have such sights to show you…” Lead Cenobite (Doug Bradley)

Connections

Film

‘Hellraiser 2: Hellbound’ directed by Tony Randel (1988)

‘Gods and Monsters’ directed by Bill Condon (1998)

Reading

Georges Bataille, Eroticism, Penguin, 2001 (1957), ISBN 0141184108

Georges Bataille, Tears of Eros, City Lights, 1989 (1961), ISBN 0872862224

Clive Barker, The Hellbound Heart, Harper Collins, 1991 (1986), ISBN 0006470653

Clive Barker, Imajica, Harper Collins, 1991, ISBN 0002235595

Sorcha Ní Fhlainn, Clive Barker: Dark Imaginer, Manchester University Press, 2017, ISBN 9781526135698

Phil and Sarah Stokes, Clive Barker’s Dark Worlds, Cernunnos, 2022, ISBN 9781419758461

Music

Clive Barker: Being Music, (1999), EMI, ISBN 1858485630

You must be logged in to post a comment.