Directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1974, 130 minutes

Young lovers Zumurrud (Ines Pellegrini) and Nur Ed Din (Franco Merli) are separated. As they search for one another through numerous misadventures they encounter a world of storytellers whose tales of demons, robbers and lovers enliven and enlighten their journey.

Pasolini avoids the usual framing device of Scheherezade who must tell stories to a prince to save her life and opts instead to approach the tales through young lovers Zumurrud and Nur Ed Din. This allows the stories to interlock and nestle satisfyingly one within another like the parts of a wooden puzzle box. Pasolini’s free adaptation of the tales is a perfectly valid approach to the material. It’s nonsense to talk of definitive versions of these stories which have changed and evolved for thousands of years. He has remained faithful to the spirit of the stories, resisting the urge to overburden the tales with political or social polemic and lets them speak for themselves. He has no need to overstate the obvious, poverty and repression are always part of life but so are love, fidelity and sacrifice.

Robert Irwin, Marina Warner and other cultural historians have painstakingly traced the evolution and influence of the Nights, including their relationship to the literature of Boccaccio and Chaucer. The fantastic imagery of the Arabian Nights has been part of cinematic spectacle since the days of Georges Méliès through Powell and Korda’s ‘Thief of Bagdad’ (1940) and, of course Ray Harryhausen but Pasolini is not content with simply showing us a picture book of oriental exotica. Like his ‘Decameron’ and ‘Canterbury Tales’ this is a film about how stories help us to better understand life. Don’t be intimidated if you have come to Pasolini’s ‘Nights’ via Harryhausen; his enchanting animated tableaux are also true to the spirit of the Nights despite their leaden acting and shaky scripts. Harryhausen’s work captures some of the magic of the original tales and has inspired a generation of filmmakers and viewers to embrace the fantastic. There may be no stop-frame cyclops or Roc birds in Pasolini’s film but you’ll recognise many of the motifs: Wise men turned to apes, lazy sons who go to sea and metal automatons can all be found here but they are presented as simply part of the tale rather than as spectacular set-pieces.

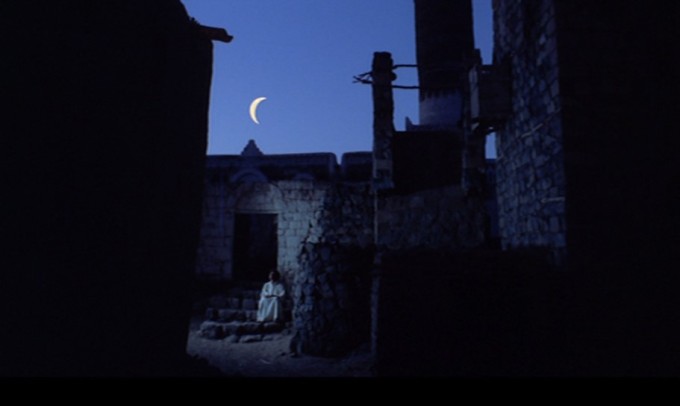

Pasolini’s ‘Arabian Nights’ feels realistic, almost documentary in places. The miraculous is ever present but it is downplayed. The film may breathe magic, but Pasolini creates wonder in a different way: Working with photographer Giuseppe Ruzzolini rather than regular collaborator Tonino Delli Colli, Pasolini presents the viewer with spectacular locations shot in luminous colour. Shimmering heat haze contrasts with sharp sunlight and the mellower shades of a desert moon. Dante Ferretti’s meticulous production design allows the abstract, rhythmic textures of Arabic design that decorate many of the locations to build their own sense of place. As a result, ‘The Arabian Nights’ has a rich, evocative otherness far removed from the Europe of ‘The Decameron’ and ‘The Canterbury Tales’. The viewer remembers the parched, monolithic desert cities of Yemen and the rain swept ruins of Nepal rather than the underwhelming Copper Knight or the rather quaint model shipwreck but ‘Arabian Nights’ is no less wonderful for its ability to conjure magic from reality rather than special effects.

This sense of veracity extends to the film’s portrayal of human relationships. Pasolini depicts a culture where sex is a gift given and taken freely. Physical love is presented with disarming intimacy and candour. There is also much laughter, the sounds of honest pleasure rather than the usual panting melodrama of most cinematic sex. More so than ‘Decameron’ and ‘Canterbury Tales’, ‘Arabian Nights’ is a film about women. In these stories women often take control of their own destinies whilst men appear as fools, driven by lust, violence or greed. The tale of Aziz (Ninetto Davoli) and Aziza (Tessa Bouché) becomes a moving meditation on the difference between male and female attitudes to love. Selfish Aziz is incapable of fidelity and his tale becomes a dialogue between the women who will ultimately cure him of his inability to distinguish between love and lust. Both women and men may wield sexual power, but desire and satisfaction are difficult to reconcile; the obsessive pursuit of sexual fulfilment can negate love and end in misery. At the centre of the film Zumurrud is beautiful, clever and resourceful, she is a slave that can choose her own master and who will ultimately become a King, crossing class and gender boundaries with ease. These women may seem fanciful to viewers more accustomed to monochrome portrayals of Islamic gender which focus on fundamentalist repression, but they provide a timely reminder of the complexities of female roles in Moslem culture. Pasolini’s inclusion of these tales more than compensates for the gender discourse lost with the omission of Scheherezade.

Despite the intricate narrative structure, the component tales are often simple: roles are reversed, there are coincidences, chance meetings and transformations. Pasolini believes that these tales express the longings and fears of the common people. In keeping with this approach ‘Arabian Nights’, like the other films in the trilogy employs mostly local non-actors. Some familiar faces re-appear, Franco Citti is cast as a demon; Ninetto Davoli plays Aziz in a more serious, balanced character role than the slapstick clown of the previous films. Franco Merli is sweet and hapless as Nur Ed Din and Ines Pellegrini gives a luminous debut performance as Zumurrud.

Tales from the Arabian Nights crossed into Europe and inspired (in part) both the Decameron and the Canterbury Tales so in returning to this primary story cycle Pasolini makes a fitting and logical conclusion to his trilogy. ‘Arabian Nights’ manages to be both earthy and mystical, a positive affirmation of life, love and the stories that we tell to help us understand them. Viewed together or individually Pasolini’s ‘Trilogy of Life’ provides a refreshing re-assertion of the things that unite all human cultures: Our ability to love as well as hate, our capacity for sacrifice as well as selfishness and the importance of laughter.

Quote

“The truth lies in many dreams” Princess Dunya’s Gardener

“What a night! God has made no other like this. Its beginning was bitter, but how sweet its end” Nur Ed Din (Franco Merli)

Connections

Film

‘The Thief of Baghdad’ directed by Michael Powell (1940)

‘The 7th Voyage of Sinbad’ directed by Nathan H. Juran (1958)

‘Decameron’ directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini (1970)

‘The Canterbury Tales’ directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini (1972)

‘The Golden Voyage of Sinbad’ directed by Gordon Hessler (1974)

‘Pasolini’ directed by Abel Ferrara (2014)

Reading

Robert Irwin, The Arabian Nightmare, Dedalus, 1983

Salman Rushdie, Haroun and the Sea of Stories, Granta, 1990

Robert Irwin, The Arabian Nights: A Companion, Allen Lane, 1994

Marina Warner, Stranger Magic: Charmed States and the Arabian Nights, Chatto and Windus, 2011

Radio

BBC Radio 4: ‘In Our Time’ 18th October 2007 – The Arabian Nights

Hello, I’m Hamid. I Study cinema in Tehran university of Art. Can I translate your review into persian and print it in our magazine?

LikeLike

Hi Hamid, you’re welcome to translate and republish this review and cite me as the author. With best wishes. Simply Sourdust

LikeLike