Directed by David Fincher, 2007, 157 minutes

A killer who calls himself the Zodiac taunts detectives as he murders, seemingly at random. Believing that the killer’s identity is hidden in the cryptic codes that he sends to the San Francisco Chronicle cartoonist Robert Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhall) becomes obsessed with finding out who is responsible.

Murder makes money. Violent crime has always been commoditised as popular culture from the moralistic prurience of the Newgate Chronicles through the rise of scientific detection in the stories of Poe and Conan Doyle to the serial killer, as popularised in Thomas Harris’ novel ‘Silence of the Lambs’ (1988) and its many imitators. Cinema, television drama and documentaries blur the boundaries between fact and fiction as branded properties from Agatha Christie to CSI rise, fall and are endlessly recycled. Thomas De Quincey, whose satirical essay “On murder considered as one of the fine arts” (1827) lampoons our fascination with violent crime, would recognise the flash mobs that flock to murder scenes and our celebrity killers. Twenty-first century technology allows anyone to become a sleuth; murders and disappearances attract theory and counter theory which is streamed globally. As crisis actors turn tragedy into performance murder victims are often eclipsed by the allure of those who break the ultimate taboo. Oliver Stone’s excoriating satire on crime celebrity ‘Natural Born Killers’ (1994) was itself accused of glamourising violence and Netflix series ‘Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story’ (various directors, 2022) was criticised for idolising its subject at the expense of his victims. Jack the Ripper has haunted popular imagination since the 1880s, thousands of pages of speculation remain in print about the identity of this nebulous killer (or killers) but a detailed study of the lives of the murdered women only appeared as recently as 2019. Unsolved crimes attract obsessive speculation and generate additional market value for as long as they resist solution and deny us the satisfying closure of a guilty verdict.

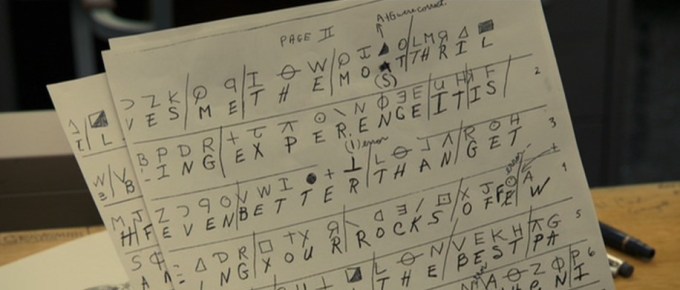

David Fincher’s first notable critical and commercial success ‘Seven’ (1995) presents serial murder as a monstrous kind of performance art, a response to the moral apathy engendered by urban misery. ‘Zodiac’ explores our fascination with serial murder and scrutinises the personalities of those who try to bring the perpetrators to justice by reconstructing a real, unsolved case history in forensic detail, laying out the clues and probing the compulsion that makes us want to decipher them. ‘Zodiac’ is a film about how we collect, interpret, and misinterpret data. Like Somerset (Morgan Freeman) in ‘Seven’ Robert Graysmith begins his work in the library with a pile of books. The Zodiac killings were scattered between various complicated jurisdictional boundaries and different detectives bring different preconceptions and levels of experience to the investigation. In this case only someone from outside the profession can see the whole picture and compile the information in a way that allows a solution to emerge. But Graysmith’s search for ‘truth’ has many false starts and dead ends. The closer we look at any sequence of events the more patterns we can see. Our ability to decipher symbols and identify patterns is part of what makes us human but it’s easy to find structure where none exists. As if to emphasise the unreliability of memory and impossibility of certitude the crimes reconstructed in ‘Zodiac’ feature three different possible killers, none of whom resemble the prime suspect.

Fincher, and writer James Vanderbilt offer their own solution to this criminal enigma, following Graysmith’s deductions but the actual identity of the criminal seems mundane when compared to the elaborate and shifting landscape of clues, hints, deductions, and theories. The sheer volume of inferences that can be made from the coded notes, choice of victims and methods of killing is staggering. Faced with a killer that seems to have no simple pattern or motivation simply amplifies the complexity of the puzzle. As if the emphasise the complexity of the case, in one remarkable sequence Fincher superimposes a flurry of coded letters and newspaper headlines over the action and the detectives appear literally lost in the shifting maze of clues and data. ‘Zodiac’ doesn’t stop at the forensics but also explores the cultural context of these crimes, illustrating the many and complex ways that crime and culture vampirize each other. The Zodiac killer may have taken his symbol from a watch logo or from the countdown cell of a cinema reel or he may have been inspired by seeing ‘The Most Dangerous Game’ (Irving Pichel and Ernest B Schoedsack, 1932). In a particularly surreal moment Detective David Tosche (Mark Ruffalo) walks out of a screening of ‘Dirty Harry’ (Don Siegel, 1971) when the links between screen killer Scorpio and real killer Zodiac become too close for comfort. In a neat touch of irony, elements of Tosche’s distinctive style inspired iconic seventies screen cops like McQueen’s Bullitt (Peter Yates, 1968) and Eastwood’s Harry Callaghan but here Harry’s bombastic delivery of justice throws Tosche’s more cerebral style, and his inability to catch his man into sharp relief.

Time becomes a significant obstacle to the solution of the Zodiac crimes so music, costume and production design must help the audience to keep pace as years become decades. Graysmith’s obsession with solving the crime is the only constant as hindsight changes the interpretation of memory and physical evidence slips further away into the past. The Zodiac crimes begin at the end of the sixties, a queasy, slippery sense of come down is evoked by the unsettling sound of Donovan’s ‘Hurdy-Gurdy Man’ which accompanies the first killing that we see. Later the screen fades to black and we hear the years slipping past in the form of radio, television news and pop tunes. Photo-realistic digital effects recreate the San Francisco of the period in precise detail and the changing city provides a backdrop to the developing case. James Vanderbilt’s screenplay works in tandem with some stunning digital effects and Donald Graham Burt’s detailed production design to place us alongside the investigators and accurately map every crime scene.

‘Zodiac’ relies on a strong ensemble cast. Jake Gyllenhall captures the hollow-eyed intensity of Graysmith’s single-minded pursuit and helps the viewer relate to a man who co-opts his young children to sift murder evidence. Robert Downey provides some welcome light relief as dissipated journalist Paul Avery, the only investigator who can recognise the chaotic elements that make the Zodiac so difficult to catch. Mark Ruffalo, Anthony Edwards (as Tosche’s partner Inspector Bill Armstrong), and Elias Koteas (as Sergeant Jack Mulanax) are outstanding. Their interrogation of suspect Arthur Leigh Allen (John Carroll Lynch, also excellent) is a masterclass of timing and nuanced performance that puts the overrated coffee shop sequence from Michael Mann’s ‘Heat’ (1995) to shame.

Amidst the exhilaration of the chase, it’s easy to forget that these were real crimes with real victims. ‘Zodiac’ shows us each killing in uncomfortable forensic detail, but we get little sense of the people whose lives were destroyed. At the film’s close we see survivor Mike Mageau (Lee Norris) identify his attacker some 22 years after the attack, his shock of recognition and acute discomfort can only hint at the damage that has been done and the trauma that he has suffered. That comfortable feeling that a criminal has been brought justice in missing from ‘Zodiac’ as it is in ‘Seven’; As so often happens in real life, there is no sense of closure here, and the case remains open.

Fincher returned to this territory with his adaptation of ‘The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo’ (2012) but it feels like a tired and predictable re-tread, despite its technical competence. His Netflix series ‘Mindhunters’ (various directors, 2017-2019) which chronicles the birth of the FBI profiling programme has little new to say that isn’t said more eloquently in ‘Seven’ or ‘Zodiac’. The theatrical cut of ‘Zodiac’ runs to 151 minutes, but the more detailed Director’s cut feels much more complete, the time passes quickly, and ‘Zodiac’ feels like a much shorter film. Unfortunately, ‘Zodiac’ was not a commercial success on release, in hindsight it stands as one of the finest films about our continuing fascination with murder and our need to seek order in a chaotic world.

Quotes

“But how do you go from ‘A is 1 and B is 2’ to figuring out this whole code?” Paul Avery (Robert Downey)

“Well, same way I did, you go to the library” Robert Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhall)

Connections

Film

‘Silence of the Lambs’ directed by Jonathan Demme (1990)

‘Seven’ directed by David Fincher (1995)

‘Summer of Sam’ directed by Spike Lee (2000)

Television

‘Mindhunter’ written by John Douglas and others, directed by David Fincher and others, Netflix, 2017

Reading

Thomas Harris, The Silence of the Lambs, 1988

Alan Moore, From Hell, Knockabout Comic, 1999, ISBN 0861661419

Brian King (editor), Lustmord: The Writings and Artifacts of Murderers, Bloat, 1996, ISBN 096503240X

Robert Graysmith, Zodiac: The Shocking True Story of America’s Most Bizarre Mass Murder, Titan Books, 2007, ISBN 9781845765316

Robert Graysmith, Zodiac Unmasked: The Identity of America’s Most Elusive Serial Killer Revealed, Berkley Books, 2007, ISBN 9780425212738

Hallie Rubenhold, The Five: The untold lives of the women killed by Jack the Ripper, Doubleday, 2019, ISBN 978-0857524485

You must be logged in to post a comment.